(VOVWORLD) - Carving wooden sculptures is a special folk art of ethnic groups such as the Co Tu, Ede, Ba Na, and Jarai of the Central Highlands. They are not just folk artifacts but illustrations of a philosophy of life. These carved sculptures are a way for the ethnic people to express their perception of human life and nature.

The Central Highlands is not only renowned for itsculture of gongs and epics, but also for its wood carved works which are rustic and simple but soulful and mysterious.Theworks are seen on staircases, beams, and rooftops of stilt houses, as well as in religious sites, and among household utensils.

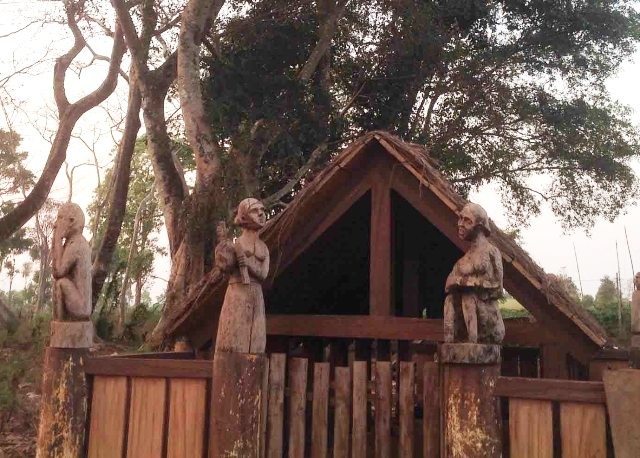

The most outstanding carvings are wooden statues around gravesites. Even village elders and researchers can’t say when these statues first appeared. For generations, Central Highlanders have built graves surrounded with wooden statues to honor the dead.

“Wooden statues of the Jarai and Ba Na are diverse. At the front of the grave, there are often statues depicting the wish for fertility, reproduction, and growth, expressed by a mother holding a child, and people pounding rice. At the corners of the grave, there are statues of sitting people crying,” said Director of the Gia Lai Museum Nguyen Thi Bich Van.

A Jarai grave replica in the Culture-Tourism Village of Vietnamese Ethnic Groups in Hanoi. A Jarai grave replica in the Culture-Tourism Village of Vietnamese Ethnic Groups in Hanoi. |

Central Highlanders believe that death is not the end but just a change from moving to still life. The newly departed spirit wanders around where it lived. Afarewell ritual called “abandoning the grave” is the last chance to see off the dead.At that point, the spirit will go to the other world. The family makes a promise for an “abandoning ceremony” at some later date, anywhere between three or even seven years. Until that date, the grave is regularly tended to and visited by family members and friends. They even eat and drink in the cemeteryin the belief that the spirit is still there.

Photographer Huy Tinh, who studies the culture of ethnic groups in the Central Highlands, said: “They often carve statues to express the feeling of the living for the deceased and remind the living to keep on doing the unfinished work of the deceased. The statues look plain and rudimentary but are soulful and meaningful.”

A grave of the Ba Na in Pleiku city in the Central Highlands. A grave of the Ba Na in Pleiku city in the Central Highlands. |

The grave statues often depict birds, beasts, household utensils, and groups of people standing, sitting, or hugging each other. The most popular statues are people sitting with their elbows on their knees, their arms holding their faces, and sad-looking eyes. People say the statues represent the relatives, sitting beside the grave to talk with the dead person. There are joyful statues of people beating drums and gongs, pounding rice, men and women having sex, and pregnant women. The grave statues illustrate their belief that death is just a start in the spiritual world.

Artisan Kso H’Nao in Kep village, Gia Lai province, is a famous carver in the Central Highlands. He said the relatives of the deceased cut trees in the forest and invite artisans to create statues. They carve the statues without any blueprint or exact measurement. Normally, one third of the statue is planted firmly in the ground. The statues expressthe feelings and thoughts of the relatives about the deceased and their view of life. Experienced artisans, mostly grandfathers and fathers, share carving techniques with their children and junior carvers.

“It’s my passion since I was 14 years old. I watched old people carve statues for abandoning grave rituals and learned from them. I carved crying faces and people with their arms holding their faces full of sorrow,” said Kso H’Nao.

Statues for worship are often placed in sacred places. But grave statues in the Central Highlands are placed in nature, under the shade of trees, with no heed to weather. Grave statues are not sophisticated in technique and polish. Still, they look lively and impressive.

“I teach young and old people, even small children to measure and chisel the outlines of the legs and the arms. But I can’t tell them how to carve the face. I see the face and imagine it in my mind. But you see differently. It’s our soul and something inexpressible. I cannot teach it to them,” said Kso H’Nao.

Ro Lan Ven, Deputy head of the Culture and Information Office of Chu Pah district, Gia Lai province, said the statues are improvised, and this improvisatory quality lends extra meaning and soulfulness to the pieces.

“The artisans follow similar motifs but always with different expression. Statues of people sitting with their arms holding their chins and mourning the deceased, a wife or a mother holding a child mourning her husband - they are placed around the grave to help ease the deceased’s loneliness in the new world,” he said.

In the Central Highlands there can be found some rather old, large graves. The statues were made of durable wood which can bear harsh weather through several decades. When the forest areas were narrowed, peoplewere forced to use low quality wood which are prone to be rotted by pests or weather.

The number of people able to carve traditional statues is decreasing because the younger generation has shown little interest in the craft. Many communities cannot make grave statues any more.

To protect the folk art, Central Highlands provinces have organized festivals and statue carving contests.

Researcher Nguyen Thi Kim Van said these events are useful for artisans to show off their skills and for young people to learn about traditions.

“Similar to preserving the art of the Gong, when the our traditions are fading, we have to organize festivals and contests to revive cultural values and customs. We aim to engage the local community in promoting and preserving their culture for future generations,” said Van.

Thanks to festivals, wooden statue–carving artisans have promoted the Central Highlands’ art to the wider artistic community. Many artisans are making an effort to introduce local culture not only to Vietnamese but also to international visitors.